Elevata porosità

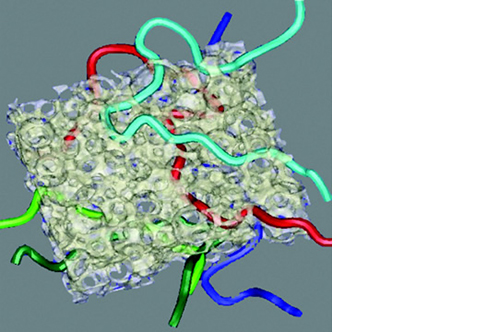

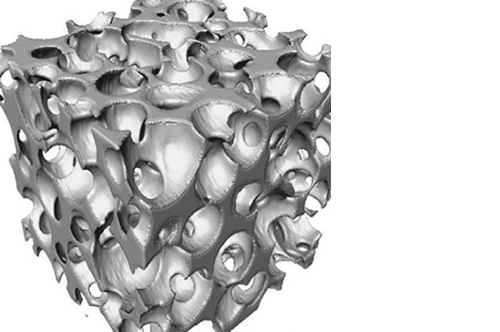

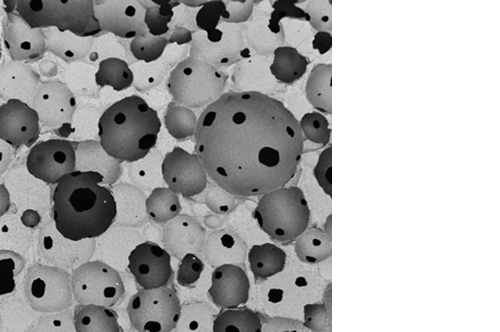

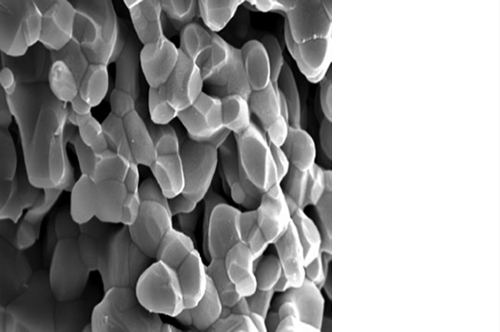

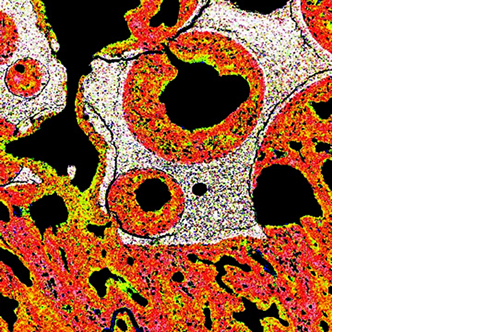

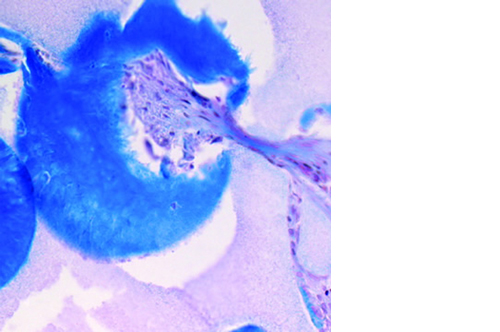

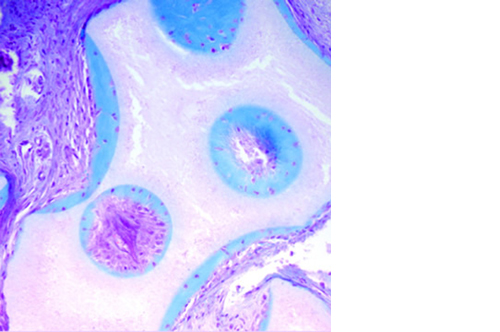

L’osteointegrazione del biomateriale e la neossificazione sono garantite da una struttura altamente porosa definita e controllata a livello macro, micro e di interconnessione dei pori.

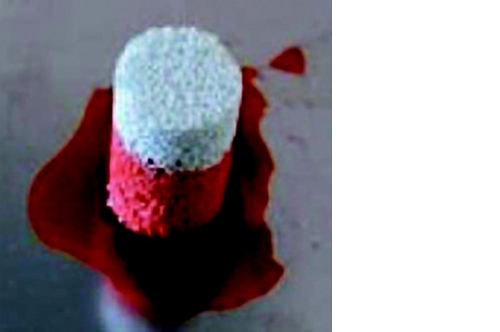

La porosità totale di ENGIpore può arrivare fino al 90%, favorendo un rapido assorbimento dei fluidi biologici e delle molecole segnale e permettendo la rapida colonizzazione cellulare indispensabile per una buona rigenerazione ossea.

Nonostante l’elevata porosità, ENGIpore è in grado di resistere a carichi in compressione al pari dell’osso spongioso.