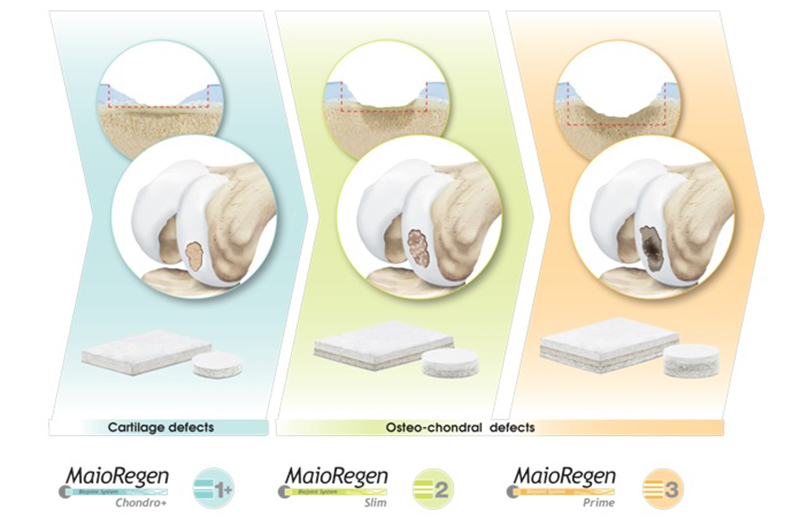

I dispositivi del Sistema MaioRegen sono indicati per il trattamento di lesioni articolari osteo-condrali e cartilaginee:

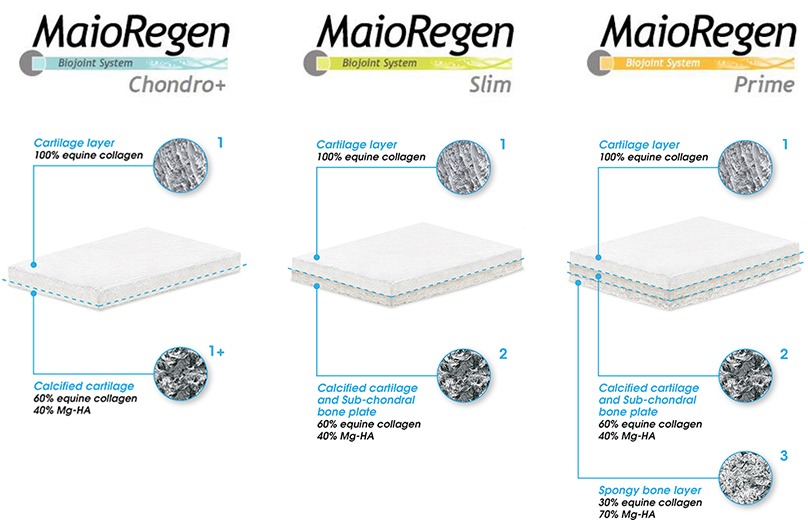

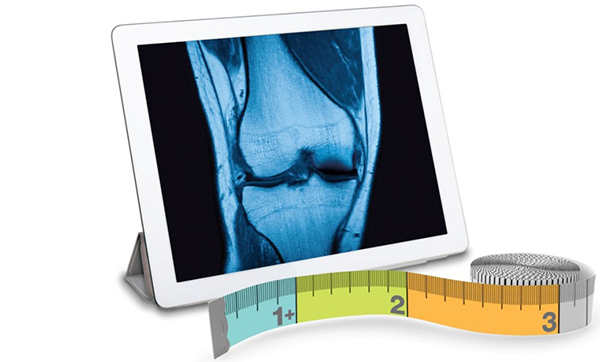

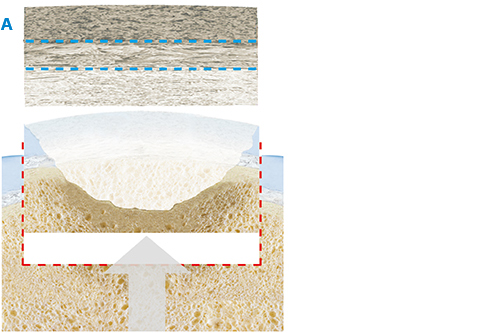

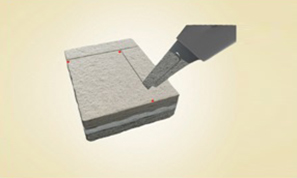

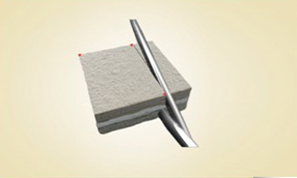

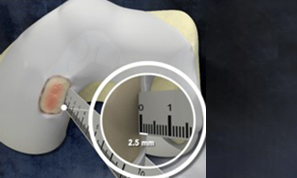

. MaioRegen Prime (scaffold tri-strato) è indicato per il trattamento di lesioni osteocondrali singole o multiple, con severa compromissione ossea, di grado IV secondo la classificazione di Outerbridge.

Le lesioni possono essere di origine traumatica, post-traumatica, degenerativa o derivanti da osteocondrite dissecante (OCD).

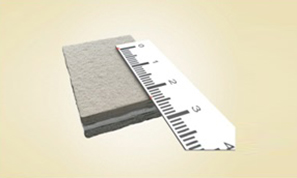

. MaioRegen Slim (scaffold bi-strato) è indicato per il trattamento di lesioni condrali profonde e osteocondrali, singole o multiple, con moderata compromissione ossea, di grado III e IV secondo la classificazione di Outerbridge. Le lesioni possono essere di origine traumatica, post-traumatica o degenerativa.

Entrambi i dispositivi sono altresì indicati per il trattamento di lesioni allo stadio di osteoartrosi precoce (Early OA), di grado I e II secondo la classificazione Kellgren e Lawrence, in assenza di osteofiti e in base al livello di compromissione ossea.

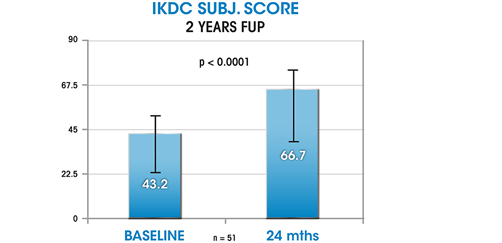

. MaioRegen Chondro+ è indicato per il trattamento per il trattamento di lesioni condrali singole o multiple, con assente o lieve alterazione del tessuto osseo subcondrale, di grado III e IV secondo la classificazione di Outerbridge, di origine traumatica, post-traumatica o degenerativa.